NGOs Urge IMO To Rethink Weak HFO Ban, Demand Stronger Arctic Protection

As the first virtual meeting of the International Maritime Organization’s Marine Environment Protection Committee (IMO, MEPC 75) opens , the Clean Arctic Alliance implored member states to amend and improve its draft ban on the use and carriage of heavy fuel oil (HFO) in the Arctic or risk implementing a “paper ban” – a weak regulation that will leave the Arctic exposed to greater danger from oil spills and black carbon pollution from HFO in the future, as shipping in the region increases.

“Instead of rushing headlong into disaster, the IMO and its Member States must make serious amendments to the draft ban on the use and carriage of polluting heavy fuel oil in the Arctic – if they approve the ban as it stands, it won’t be worth the paper it’s written on”, said Dr Sian Prior, Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance.

“IMO Member States must realise that unless they remove or amend the exemption and the waiver clauses, and bring forward the implementation dates, the HFO ban as currently drafted will leave the Arctic unprotected in the years to come. In fact, it is likely that the volume of HFO used and carried will increase, resulting in a greater risk to the Arctic from HFO spills and black carbon pollution for the next decade”.

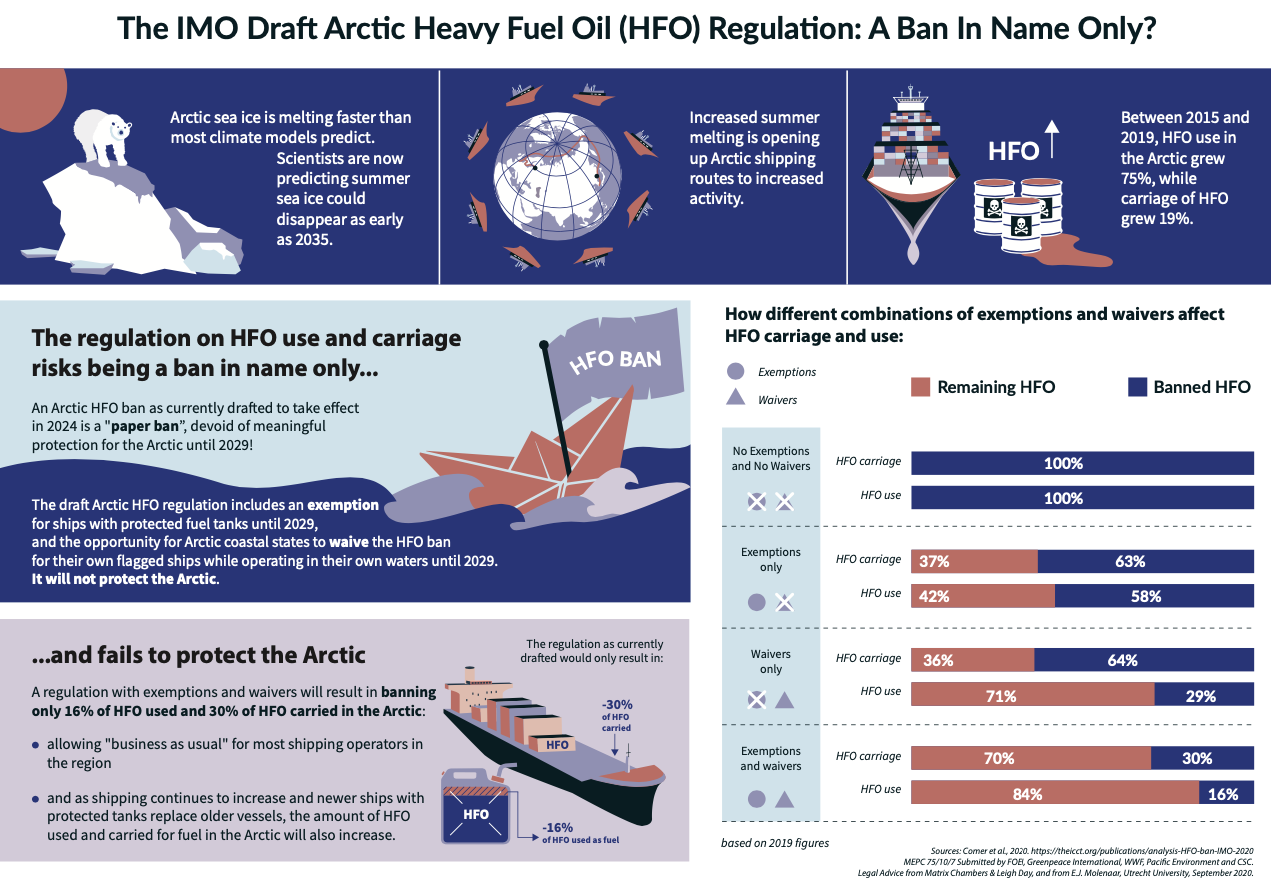

At the IMO’s PPR 7 subcommittee meeting in February 2020, the IMO and its member states developed a draft regulation prohibiting the use and carriage as fuel of HFO by ships in the Arctic. However, the inclusion of loopholes in the draft regulation – in the form of exemptions and waivers – means that a HFO ban will not come into effect until mid-2029, leaving Arctic communities, Indigenous peoples and ecosystems exposed to the growing threat of HFO spills for the whole of the 2020s – nearly a decade .

“Increased shipping in the Arctic poses great risks, and Arctic communities are seeing its negative impacts from debris and marine mammal ship strikes. Banning HFO from the Arctic is the right thing, and IMO Member States must ensure that it is a true ban. Exemptions and waivers allow business as usual. It is upon all nations to consider the impacts to people who live in the Arctic and make their living from the waters of the Arctic to implement an HFO ban to lessen the myriad threats we in the Arctic face”, said Austin Ahmusak, marine advocate for Kawerak, Inc, Alaska, which works to assist Alaska Native people and their governing bodies to take control of their future.

As drafted, the five central Arctic coastal states will be able to issue waivers to their own flagged ships and by-pass the ban. The regulation is not flag-neutral, and it will create a two-tier system of environmental protection and enforcement in the Arctic, along with lower standards and negative environmental consequences in the Arctic’s territorial seas and exclusive economic zones. This version of the ban could also potentially lead to transboundary pollution.

According to recent analysis by the International Council on Clean Transportation, as currently drafted, the regulation will only reduce the use of HFO by 16% and the carriage of HFO as fuel by 30% when it takes effect in July 2024, and will allow 74% of Arctic shipping to continue with business as usual. Between July 2024 and July 2029, when the ban becomes fully effective, the amount of HFO used and carried in the Arctic is likely to increase as shipping in the Arctic increases, and as newer ships replace older vessels and are able to take advantage of the exemption or change flag and seek a waiver from the ban.

Earlier this month, on November 6th, Norway announced a proposal to ban HFO from all the waters around the Arctic island archipelago of Svalbard. HFO has already been banned from Svalbard’s national park waters since 2015, and has been banned throughout Antarctic waters since 2011 .

It is not just the risk of HFO spills that concerns the Clean Arctic Alliance; heavy fuel oil is a greater source of harmful emissions of air pollutants, such as sulphur oxide, and particulate matter, including black carbon, than so-called “alternative fuels” such as distillate fuel and liquefied natural gas (LNG). When emitted and deposited on Arctic snow or ice, the climate heating effect of black carbon is up to five times more than when emitted at lower latitudes, such as in the tropics. The US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) recorded the monthly average ice extent for October was the lowest in the satellite record, while the summer sea ice extent was the second lowest on record .

Recently published work by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN body responsible for regulating international shipping, shows that globally shipping black carbon emissions have grown by 12 per cent between 2012 and 2018 , while work from the International Council on Clean Transportation found that in the Arctic black carbon emissions from the Arctic shipping fleet grew by 85 per cent in only four years between 2015 and 2019 .

The decline of Arctic sea ice is expected to open up little used shipping routes including the Northern Sea Route – across the top of Russia – to ships trying to find a faster, cheaper route between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. But the decline of sea ice and greater accessibility to ships increases the risk of accidents, particularly due to the hazards of navigating poorly charted waters. As well as the dangers of HFO spills – an Arctic oil spill would prove nearly impossible to clean up, the burning of fuel such as HFO has a direct and localised impact for the Arctic sea and glacier ice. When black carbon particles fall on ice, they reduce its ability to reflect light and heat, which leads to accelerated melting. As the snow and ice melts, the darker surface of the land or the sea beneath continues to absorb heat. In short, the use of HFO by Arctic shipping contributes to the acceleration of multiple feedback loops that are contributing to dramatic changes in the Arctic and elsewhere.

Despite the dramatic changes occuring in the Arctic due to global heating and the risk to the Arctic from emissions of black carbon from shipping, black carbon will not be addressed at MEPC 75.

“The IMO has spent nine years already discussing black carbon but has so far failed to agree any concrete measures to reduce emissions. The Clean Arctic Alliance wants to see the IMO develop and adopt a resolution which would set out recommended interim measures to reduce black carbon emissions, ahead of completion of the work to identify and implement one or more black carbon abatement measures”, said Prior.

“The Arctic is changing before our eyes and those changes will have repercussions for all of us” continued Prior. The contribution of black carbon to global heating especially when emitted close to snow and ice is significant and it is imperative that all sources are rapidly eliminated.”

The Clean Arctic Alliance is calling on the IMO and its Members to step-up and take action which will urgently reduce and eliminate black carbon emissions from ships operating within or near to the Arctic. By switching from HFO or very low sulphur fuels (VLSFOs) to alternative cleaner fuels emissions of black carbon can be reduced by 30 – 45%. Then the installation of an efficient particulate filter will increase the reduction of black carbon emissions by over 90%.

MEPC 75 is also scheduled to make a big decision on greenhouse gas emissions. In October, the IMO’s working group on reducing GHG emissions developed an extremely weak proposal known as “J/5.rev1“ that at best would shave 1.3% from the business-as-usual growth pathway of 15% by 2030. In short, unless delegates reject this weak deal, IMO will endorse a climate plan that sees emissions from ships keep growing for several decades – backtracking on its own commitments made in 2018 to strive for a short-term peak in emissions followed by reductions.

If the global shipping industry were a country, it would lie 6th in the carbon emitter’s rankings, above Germany – with 1 billion tonnes of emissions a year, around 3% of the global total.

These emissions have a direct impact on the Arctic, which is warming twice as fast as anywhere else on Earth due to global heating. It is well known that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic – loss of sea ice is likely to drive instability in the polar regions and upset weather patterns while the melting of Greenland’s ice caps is set to raise sea levels in port cities around the world.

What to expect from MEPC 75:

The draft Arctic HFO ban regulation will be discussed during the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee from 16-20 November 2020 (MEPC75), which will be the first MEPC meeting held virtually. During the meeting:

- NGOs will draw attention to the inadequate impact and effectiveness of the draft regulation banning the use and carriage of heavy fuel oil (HFO) by ships in Arctic waters.

NGOs will highlight recently published work indicates that loopholes in the draft regulation mean that only 30% of HFO carriage and 16% of HFO use would be banned when the regulation comes into effect as proposed in 2024, and incredibly, that it is likely that the amount of HFO carried and used in the Arctic will increase following the ban taking effect.

- Despite the dramatic changes occuring in the Arctic due to global warming, the risk to the Arctic from emissions of black carbon from shipping will not be addressed at MEPC 75. The Clean Arctic Alliance will however continue to push for a commitment to a MEPC black carbon resolution which would set out recommended interim measures pending completion of IMO work to identify and implement one or more black carbon abatement measures.